‘Worked solutions’ are a relatively modern phenomenon and are symptomatic of mass education. With ample time available, a master would guide an apprentice through the solution to a problem by the Socratic method, and would adapt to the apprentice’s approach. There would be no need for a ‘worked solution’ because the only meaningful solution for the learner would be the one they generated themselves.

On a mass scale, we can only aspire to emulate that experience through automation; we are working on that, but we are not there yet. Hence ‘worked solutions’ are an important part of the current education process.

The growth of class sizes has been invidious over the last half century, and the growth of the role of worked solutions likewise. We have not established clear guidance for students on the discipline required to make healthy use of this resource. I like to think everyone knows that you shouldn’t look at worked solutions unless you really must, and even then it should be done very cautiously. But I recently asked a student about their exam preparation method and they said they had the questions and the worked solutions open together, the first time they saw the material. This is shockingly bad and illustrates the need to embrace this issue – we must discuss discipline with our students. It’s not obvious to some, or even many, of them.

The framework I want to use to discuss the use of worked solutions is the tension between symmetry, independence, and trust. Symmetry refers to student and teacher accessing symmetric data. Independence is knowing when to reveal supporting information that is available; it is being a self-regulated learner rather than depending on a teacher to regulate activities. And trust, between student and teacher, which is essential for a healthy education, is tested differently depending the level of symmetry and (in)dependence.

‘Real’ problems are those when a solution is not available to the problem solver. The solver must understand the problem, plan their solution, execute it, and then look back on the solution to ensure it is valuable and to learn from the experience. These are the four steps of problem solving articulated by George Polya. At no point is a ‘worked solution’ a part of this process. Whether a problem is simple and abstract, like a basic maths exercise; or complex and applied, like the development of an engineering system, the mindset and craft we are trying to inculcate in the student is one of solving problems when the solution is not known. It seems logical, therefore, to start from a position where access to worked solutions is not justified until one can provide the justification. I will begin, then, from the position that there should not be a symmetry of information between the student and the teacher. The student should not have a ‘worked solution’ – unless we can argue otherwise.

We have established that in practice students frequently get ‘stuck’ during problem solving. A good teacher, following Polya’s method, will ask questions that are as general as possible. In one of Polya’s examples the question ‘Do you know a method that might help?’ is considered good, while ‘Could you try the Pythagorean theorem?’ is considered bad (for reasons clearly articulated on p.20). This suggests that even if some ‘information’ is revealed to a student, then it should be limited, and general as opposed to specific. So some information is shared, at a point judged by the teacher; but full symmetry is ruled out.

There is an implicit assumption in the above approach, which is that there is mutual trust between the two parties. The teacher trusts that the student really wants to solve the problem, and the student trusts that the teacher wants to help them. These are both very tenuous ideas in practice. Students attend school or university with very complex motivations that are rarely aligned with the teacher’s purest view that learning (their subject/discipline) is an existential pleasure and a pursuit worthy of one’s time and effort.

The misalignment between the student and teacher’s intentions can lead to misunderstanding about the intent of the teacher. More likely, however, is that the student simply will not have access to the teacher at all – at least, not at the point in time where help is needed. Not when they get ‘stuck’. The teacher’s behaviour is then judged in absentia based on what information is provided in written materials (or videos etc.); if the teacher does not provide ‘adequate’ information, as judged by the student, then distrust can grow. The student can become frustrated. Understandably so.

So the motivation for a teacher to withhold worked solutions is justified from the teacher’s perspective. However, the student’s interpretation can be different and, understandably, lead to mistrust when information is withheld and the teacher is not present.

A possible solution to the impasse as described so far, is for the teacher to provide written solutions on the condition that the student exercises discipline. Providing more symmetric information can engender trust and foster the good habits that an independent learner needs. This requires discipline in the student. Is a student independent enough to withhold their own access to the information until the time is right?

To begin with, is a student even aware that they are on a path to independence? Often, no. So the first thing we need to do is to encourage discussion around discipline and independent learning when considering worked solutions. But, even then, when suitably briefed, what do students actually do?

In a recent development, I made worked solutions available to my students without delay and without controlling access. I wanted to express trust in the students and I expected them to make appropriate use of their access. I used an online system that delivered both the questions and the solutions. After a few years of developments, some careful restrictions were in place; this includes revealing one step of the solution at a time – which has proven very popular.

We are still grappling with processing the data on how students use the information. Currently – subject to questions over our ongoing data analysis – it seems that most users occasionally struggle to exercise discipline. I.e. they access the final answer earlier than the time suggested to spend on the question. The proportion of users breaking this ‘rule’ usually increases with the difficulty of the question, and often with the position in the homework set (later questions, less discipline). We’ll continue to research this issue.

Given the concern over the level of independence of a student, what should a teacher do? Should a teacher provide worked solutions? If so, how? Traditionally worked solutions are a PDF that is withheld for a fixed time; but that isn’t necessarily a good option, and new options exist that can be more customised with technology.

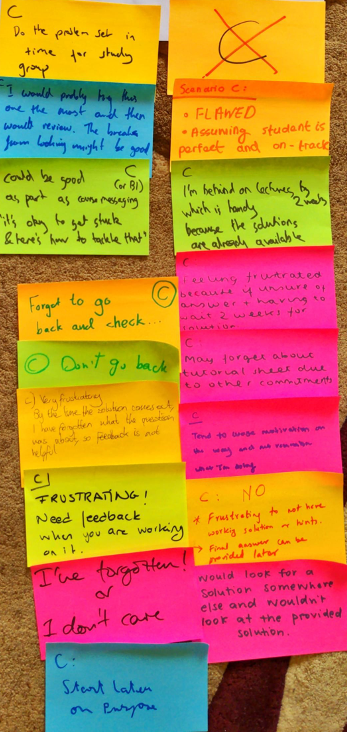

We gathered a group of students, teachers, and support staff to discuss the issue. In four separate groups, each with a diversity of members, we asked participants ‘what would you do in this scenario?’ for different scenarios. There were three basic scenarios, one of which had two variants. Each scenario describes when a student would gain access to worked solutions.

- Open access

- Access a certain time after the student first accesses the problem description.

- The student chooses the time delay

- The teacher chooses the time delay

- Access after a particular calendar date (e.g. two weeks after the questions are released).

We asked participants The basic trends that emerged from the group discussions are summarised in the table below.

| A (open access) | B1 (time delay after opening; time controlled by teacher): | B2 (time delay after opening; time controlled by student): | C (delayed release based on calendar, e.g. 2 weeks, set by teacher): | |

| Pros | meets needs, timing is right, no trust issues | emphasis on spending time; supports good study habits. For some students it’s good for discipline and trust. | healthy focus on how to study; good discipline. | could encourage a healthy break and then review. Could fit will with tutorial system if good messaging. |

| Cons | requires discipline; many lack discipline; may need a barrier | most users would open it earlier, then wait for the solutions to be available before starting. Breach of trust. Poor discipline. | Can be gamed, e.g. set to 1 min; or wait as per B1. | Very strong negative reaction to this! Frustration. Lack of trust. May forget to look. May have forgotten about it by the time its released. May just work two weeks behind to have ‘instant’ access. |

| Conclusion | Mixed | Worse than Scenario A because it’s the same in practice but there is a negative affect on teacher-student relations. | Good on balance, with some limitations. Good for trust, good for discipline, good for symmetry. | Negative overall. |

We then had a critical discussion as a larger group about what we had expressed. Some critical points emerged. Firstly, timing isn’t the only important factor. The order and method of work is important, e.g. first work, then check hints, then answer, then solution. We could, for example, make hints available immediately but not the answer/solutions. Practically speaking, access to the solutions could be dependent upon sensing a ‘reasonable effort’ by the student; current options are crude (e.g. 3 incorrect attempts), but future technology could be more discerning.

Secondly, it’s not just about the problem at hand, it’s about a conscious approach to study more generally. Thirdly, our limited, but growing, use of ‘auto feedback’ is important. If there are reliable, 24/7 answer checkers, then this changes the context. As the quality of this auto feedback improves, access to the solutions will become less critical – much like the master and apprentice.

Fourthly and lastly, cohorts are large; and there are different years of study; student needs are diverse. Rather than looking for a ‘one size’ approach; we should be personalising the approach. For example, how students study, how far through the course they are. Some of these aspects will not be practically actionable in the immediate future but it is important to bear in mind as we develop technology further. Our direction is towards adapting to the personal needs of the student.

The discussion is interesting in itself, but also has a practical destination: how should we design online platforms for self-study? We concluded that the teacher should be given three options:

- Open access (A)

- Open access but a warning sign appears if adequate time has not elapsed (a softer version of B)

- Close access until the teacher flicks a switch (C)

I will be using the second option, but other teachers can choose their own approach.